Exhibit of the Week: World War One public information poster

It’s a bright day, and the aircraft above you is flying high, so all you can see is a black shape silhouetted against the sky – how would you know whether it was one of ours, or one of theirs?

That was the problem facing the people of this country back in 1915 – attacks from the air were a terrifying new possibility, something that had only very recently become possible.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

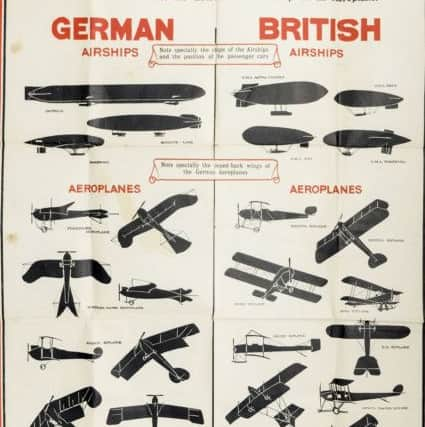

Hide AdPrinted by Sir Joseph Causton and sons of Eastcheap, EC, under the authority of His Majesty’s Stationery Office, this two penny ‘public warning’ poster attempted to clarify this difficult dilemma.

It advises the public to ‘familiarise themselves with the appearance of British and German Airships and Aeroplanes, so that they may not be alarmed by British aircraft, and may take shelter if German aircraft appear’.

Should hostile (that’s HOSTILE) aircraft appear, the reader was advised to take shelter immediately in the nearest available house, preferably in the basement, and remain there until the aircraft had left the vicinity. Don’t stand about in crowds, they were told (presumably this would make them a target) – and under no circumstances touch unexploded bombs.

They’re also told that any sightings of hostile aircraft should be reported to the nearest ‘Naval, Military or Police Authorities’, by ‘Telephone’, including details of the time of appearance, direction of flight, and whether the aircraft was an airship or aeroplane.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

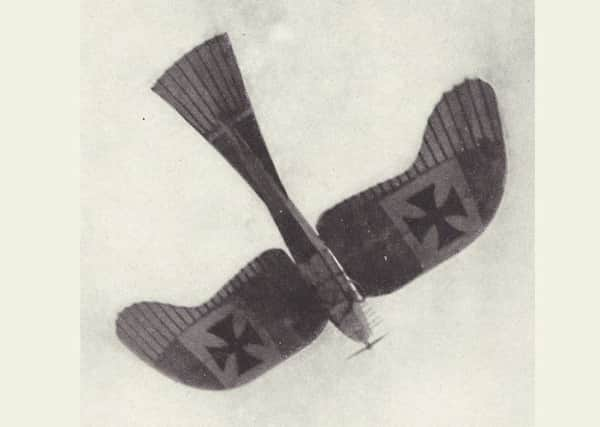

Hide AdAnd as with so many things military, the German aircraft are considerably sleeker and more threatening than their British counterparts, which err towards the chubbier and cosier: the Rumpler Taube Monoplane is distinctly hawk-like, while the Sopwith Tractor biplane looks much more friendly and approachable. Appearances can, of course, be deceptive.

Airships were not to last too long as military aircraft – they were far from agile at best, and at worst, they were downright dangerous. No one who has ever heard it can forget the distress of American commentator Herbert Morrison when the German airship Hindenburg, coming into dock in New Jersey in 1937, suddenly and dramatically burst into flames and crashed killing 36 people.

It’s one of the world’s most famous aircraft disasters – but another equally dramatic airship tragedy had taken place much closer to home 16 years earlier.

The R38, commissioned during World War I but built after it, was being housed at Howden near Hull prior to being flown across to America, which had bought her for their navy from the British government.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdVarious faults with her infrastructure had been identified, but the government was keen to unload the airship, which was considered expensively surplus to requirements, and cut corners on the testing.

On 23 August 1921 she was due to fly from Howden to Pulham in Norfolk where she could be moored to an airship mast before the flight to America, but thick fog on the Lincolnshire coast meant she had to turn back. Keen not to waste the journey, the crew carried out trials on the way back to Hull including, as they reached the city, simulated sharp turns at speed.

The manoeuvres proved too much for her, and she broke in half: her front half exploded, and her rear half fell into the Humber. People rushed out in boats to help, but to no avail: there were 49 people on board, both Britons and American crew who had come over to take her home – 44 of them died. Many of those who died are buried in a mass grave in Hull’s Northern Cemetery.

The disaster marked the end of the UK military’s airship activities.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis World War I public information poster is part of the Scarborough Collections, the name given to all the museum objects and artwork acquired by the borough over the years, and now in the care of Scarborough Museums Trust. For further information, please contact Collections Manager Jennifer Dunne on [email protected] or 01723 384510.