Nostalgia: Power of the three Twelves

The two bailiffs were the town’s supreme governors. During their year they sat as justices of the peace in three different courts: of quarter sessions, of pleas and of the leet or sheriff’s tourn. Held four times a year, the quarter sessions dealt with criminal offences against the Crown and disturbances of the peace, such as theft and burglary, assault and affray. The court of pleas sat almost every day to try civil cases such as debt and trespass. The sheriff’s tourn or court leet met twice a year to deal with offences against the borough’s bye-laws on highways, weights and measures, market rules and breaches of licence regulations. Finally, the two coroners, who had been bailiffs the previous year, investigated sudden, accidental or unusual deaths in the borough.

Most of our information about day to day events in Scarborough during the early 1600s comes from the proceedings of the quarter sessions and the sheriff’s tourn. The four chamberlains were responsible for the town’s financial affairs and their records were kept separately. All of Scarborough’s corporation records are now kept in the County Record Office at Northallerton.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Common Hall had almost absolute authority over the affairs of the borough and its people. Every St Jerome’s Day, September 30, it chose its own members, its own chief executive officers and an army of junior employees. Scarborough had its own gaoler to keep the prison; its warrener, to look after its ground game; its netherd, who was responsible for the town’s cattle and horses grazing on Weaponness and in Ramsdale and the town bull which he kept on the Common; the pindar, who put stray animals into his pinfold; four pasture masters, who collected fees from animal owners. Scarborough also had up to four constables to keep the peace and Falsgrave had its own constable, bye-law man and warrener.

Scarborough’s Thursday and Saturday market regulations were enforced by two alefyners who tested the quality and measurements of ale and beer for sale; two breadweighers, who did the same services for market bread; and leather searchers and sealers, who inspected the quality and dimensions of market leather. The borough even had its own cook who prepared feasts for the Common Hall and for special occasions such as marriages, baptisms and funerals.

As far as the town’s industries, trade and property were concerned, the Common Hall leased out monopolies, privileges and tenancies, usually to its own members. There were monopolies for salt-making, blubber-rendering, tithe collections, pier charges and brick-making, to name but a few. All trades were controlled by a restricted number of guild members who in Scarborough were the bakers, butchers, coal porters, masons, blacksmiths, carpenters, glovers, weavers, tailors, skinners and cordwainers (shoemakers).

Maritime commerce was conducted by the Society of Owners, Masters and Mariners, set up in 1602 by 35 founding fathers who were nearly all Common Hall members. Every owner whose ship had made a successful voyage paid a contribution to the Society’s funds, which increased in value as Scarborough’s carrying trade grew. On occasions, the chamberlains actually borrowed money from the Society.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

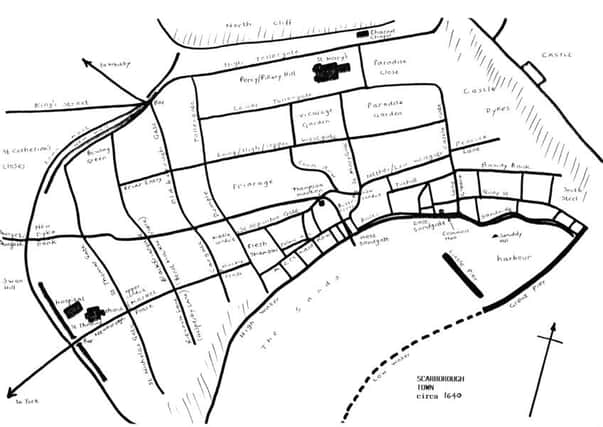

Hide AdThe Corporation possessed an enormous portfolio of valuable properties which were tenanted on seven-year leases usually by those in the three Twelves. Besides the extensive pastures of Weaponness and Ramsdale, there were the town’s three water, one horse and one wind mill; the Wheatcroft farm of 50 acres; the Mere and its adjacent closes in Burtondale; and dozens of grazing and plough lands such as the Garlands, St Catherine’s Closes; Swan Hill; Bull Lane (Aberdeen Walk); the Elriggs (Prince of Wales Terrace); Northstead Lane; New Dyke Bank (North Street carpark); Colescliff (Alexandra Gardens); and many, many more.

The Corporation was responsible for the town’s grammar or high school, then sited in the Charnel Chapel opposite St Mary’s. Its headmaster was appointed and paid by the Common Hall with the approval of the archbishop of York.

The Common Hall also appointed St Mary’s churchwardens and the overseers of the poor whose duties included putting orphan children into apprenticeships, doling out charities to paupers and supervising the poorhouse and its inmates.

The town’s public water supply was also in the care of the bailiffs. It was taken from Falsgrave’s natural hillside springs and through underground lead pipes passed down to three conduits or open troughs. Contracts were made with local plumbers who guaranteed to maintain the supply, winter and summer. Anyone who interfered with the flow or polluted the water was severely punished. Through the courts, the bailiffs were also required to keep streets, markets and sewers clean and free of obstruction, to prevent encroachment on public paths and highways, and to protect the fish and flesh shambles from misuse or damage.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn times of plague, the bailiffs imposed curfews, quarantined infected houses, built pesthouses and fed their occupants. No one was allowed to enter or leave the borough without their permission or to take “strangers” into their homes.

At the quarter sessions, breaches of the Sabbath were heard and punished. It was forbidden to sell ale or drink it, play indoor or outdoor games, even walk on the sands during Sunday services. Persistent offenders were heavily fined or even excommunicated from the established church.

Finally, the bailiffs were the moral guardians of the local community. They punished swearing, blasphemy, incest and fornication. Fathers of bastard children were required to maintain them and their mothers until they were old enough to be apprenticed. Their mothers were stripped naked to the waist and flogged through the streets of the town until their bodies were bloody.