Nostalgia: Roles, lives and livelihoods of the fairer sex

First, all three were untypical of their time, in the sense that they belonged to a small, privileged minority. We know much about them because they were ladies, the daughters and wives of well-to-do gentlemen. As such they were literate and both Lady Margaret and Mrs Thornton wrote down accounts of themselves which fortunately have survived. But they are extremely rare.

When Antonia Fraser, the historian, told one of her distinguished male friends that she was writing a book to be called (ironically) The Weaker Vessel on seventeenth-century women, half-jokingly, he replied, “Were there any women in England at that time?”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

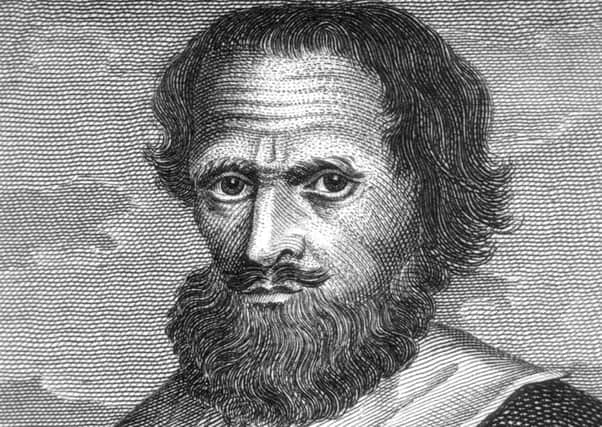

Hide AdDuring William Shakespeare’s lifetime the very idea of equality between the sexes was totally unthinkable. Society as a whole was hierarchical: it had always been so and it would remain so forever. Even men born of the same parents were graded according to their age: an eldest son succeeded to his father’s titles, status and property; a younger son would have to make his own way in the world or marry a rich heiress. As for man and woman, it was indisputable that God had deliberately created one bigger, stronger and more intelligent than the other (an average adult male was 5’ 7” tall and an average woman no more than 5’ 2”). At the beginning of the century, a London physician, Simon Forman, named 70 diseases known only to women and not men, and explained that these were God’s punishments for Eve’s corruption of Adam!

A list of what women were not allowed to be or do 400 years ago is lengthy. They were denied votes in parliamentary and municipal elections, as were most men. Parliament was exclusively male. So were the professions. Universities, the Inns of Court and schools were for males only. Only men could be justices of the peace, lawyers, priests, doctors or surgeons. There were only a very few cases of female churchwardens, none of them in Scarborough. The only “medical” practice open to females was “midwifery”. Even crafts, trades and businesses were closed to women, unless their fathers or husbands practised them. By definition all freemen were male and in most communities only freemen had local licences to make, buy or sell. In Scarborough, women seem to have been restricted to beer-brewing and ale-house keeping.

At every social level, an unmarried woman was subordinate to her father, brother or any male in the family and a married woman to her husband. All property belonged to the husband. A married woman could not travel outside her home, enter a legal contract, or make a will without her husband’s consent. In law, a man might beat “an outlaw, a pagan, a traitor, a servant, an apprentice or his wife”, in that order!

However, there were compensations for being a wife rather than a single or widowed woman. You could bear children by your husband legally: unmarried mothers were stripped and whipped in public. When your husband was absent on business or at sea you would be effectively head of the household with servants and apprentices as well as children under your authority; and you would be in charge of cooking, cleaning and shopping for supplies.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdYour husband would usually be the choice of your parents and his, but if he belonged to a higher status you would be elevated to his level. Lady Margaret Hoby was the only heir of a wealthy but relatively lowly landowner and she was promoted to their standing when she married three younger sons of the aristocracy. In her case this was made possible only by her father’s dowry money which bought an estate for the newly-married couple.

On the other hand, there were dangers for a woman who was chosen only for her dowry. She might be tied permanently to a man who was unfaithful, violent or prodigal. In the words of one current saying, “They that marry where they do not love, will love where they do not marry”. In this respect, Lady Margaret’s experience was not as exceptional as it seems to us. Her first “bought” husband, a younger son of the earl of Essex, in effect abandoned her. She was fortunate that he encountered a cannon ball so quickly. Her second “bought” partner, a scion of the Sidney family, suited her well and she was unlucky that he died prematurely. As for the third, there was only mutual respect between her and Thomas Hoby; and it was only his frequent, long absences from Hackness leaving her complete freedom to manage the estate and their Calvinism in common that made the marriage work.

Sir Hugh Cholmley of Whitby had seen his future wife, Elizabeth, only once distantly before their wedding was arranged between their fathers. In his case, Elizabeth’s dowry of £3,000, £2,500 “in redy money in one day before marridge” and security for another £500 after six months, helped to settle his father’s most pressing debts. Yet though in many respects the couple were poles apart, Elizabeth set out to “civilise” her tearaway, improvident husband from the bleak North and eventually succeeded. The two became inseparable and Hugh never recovered from the shock of her death after 33 years and died within two years.

In contrast, Alice Thornton married out of desperate self-preservation. She came from a privileged, wealthy family, impoverished by bad luck and politics, and as a Royalist without male protectors she was at the mercy of marauding, rampant Scottish soldiers in the neighbourhood of Richmond. Her husband, William Thornton, was a weakling in every way, but he offered her a safe home and secure income. Between 1651 and 1668 she bore him nine children of whom only three survived and at the age of 40 she was saved from further dangerous pregnancies by the death of William.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA widow, especially a wealthy widow, enjoyed more freedom than any others of her sex. Alice Thornton lived on for another 40 years to the ripe old age of 80. Thomasin Farrer lost her husband about 1628 and died in 1654. Throughout all these years she seems to have lived in relative comfort in the same house in Scarborough during two civil wars.

Finally, the main danger for a woman living alone, whether spinster or widow, was to be accused of witchcraft.