Nostalgia: Royal approval to entertain

It was at this critical moment in Shakespeare’s career that he wrote Hamlet, one of the most intriguing, complex characters in literary creation. Soon afterwards, in September 1601, came the death of his father at his home in Stratford. Now head of the family household, William inherited John’s house and land and became a property owner of substance. The next year he put down £320 for 107 acres of farm land north of Stratford.

The death of Queen Elizabeth and succession of King James in 1603 turned Shakespeare’s company into the King’s Men with licence to “exercise the art and faculty of playing comedies, tragedies, histories, interludes, morals, pastorals and stage plays” for the pleasure of the public and the Crown. As a result, Shakespeare became a member of the royal court with the title of Groom of the Bedchamber. During the next 13 years, the King’s Men played 187 times at the court of James I.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBy 1604, at the age of 40, Shakespeare had written his final true comedy. His mood was now usually sombre, sober and grave: battle-hardened and world-weary, his outlook was now sceptical, if not cynical. Forty years of age in 1604 was the equivalent of 80 today: it was beyond the average life expectancy and well beyond that of the inhabitants of the disease-ridden, polluted, lawless capital.

Yet he had lost none of his bold, rich originality. Othello was the first “noble” black man to appear in Western literature at a time when the King’s chief minister was complaining openly of the number of “blackamoors” who were “infiltrating” English society. Othello was the most sympathetic of all Shakespeare’s tragic heroes.

In July 1605, as further proof of his profitable success, he spent £440 on the “tithes of corn, grain, blade and hay” in Stratford town. He no longer needed to write plays for the money: his income from property and shares was sufficient to support a family in comfort. Such was his fame by now that his name was being printed next to plays he had not written, such as A Yorkshire Tragedy.

Shakespeare’s originality was that of a selective magpie. For his many histories he drew heavily on Holinshed and Geoffrey of Monmouth, but he was never slavishly dependent on them or any one source. He adapted received narratives to suit his own purposes. For instance, The True Chronicle History of King Leir has a king with three daughters, of whom one called Cordelia refuses to accept her father’s choice of husband; but it has no storm and no fool, and King Leir was neither old nor mad and neither he nor Cordelia die. Perhaps what is most amazing about Shakespeare was his productivity: within 18 months after Hamlet, came three great tragedies, Othello, Lear and Macbeth.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne of the many more credible stories about Shakespeare’s life describes how between London and Stratford he often slept overnight at the Bull, a tavern in Oxford; and that there in 1605 he fathered another William by the Bull’s beautiful landlady, Mrs Jeanette Davenant. Sir William Davenant, as he eventually became, revived Shakespeare’s plays after the Restoration, introduced females to the London stage, and founded theatres at Covent Garden and Drury Lane before his death in 1668. Jeanette is my favourite candidate for Shakespeare’s “dark lady” of the sonnets and his Cleopatra.

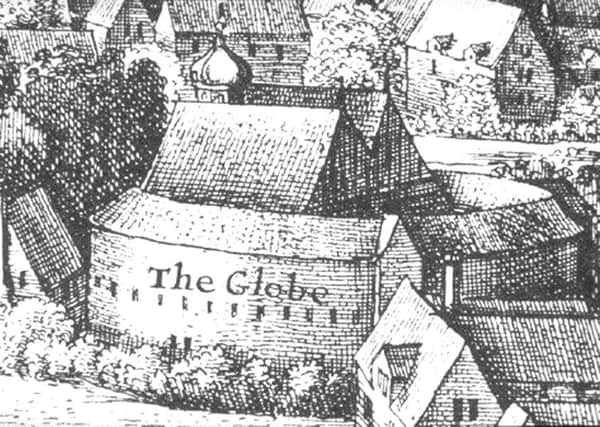

From 1608, Shakespeare had two theatres: in summer, the roofless Globe and in winter the covered but much smaller Blackfriars. With no ill-behaved “groundlings” to disrupt proceedings and a much more sophisticated seated audience of 700 paying sixpence each, he was able to write more intimate scenes for Blackfriars than for the Globe. The result was plays such as Cymbeline and The Winter’s Tale.

Shakespeare’s last play The Tempest was inspired by a contemporary shipwreck and rescue and an essay by Montaigne which praised the primitive simplicity and innocence of the noble savage. Caliban was probably based on his description of the Caribs who had once populated the West Indies.

After Shakespeare had finally contributed some scenes to the royal-command play about Henry VIII in 1613, a spark fired from a stage cannon ignited the thatched roof of the Globe and destroyed the whole building within an hour. The theatre was soon re-built, this time with a tiled roof, but Shakespeare had penned his last solo play. He retired to Stratford into the medical care of his son-in-law, John Hall, an eminent physician.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdInappropriately, since he had never been a tippler, Shakespeare died after carousing on pickled herring and Rhenish wine with his old friends, Ben Johnson and Michael Drayton. On April 23, 1616, they were celebrating his 52nd birthday.

The “second-best bed” Shakespeare famously bequeathed to his widow Anne was their marital bed: the best bed at New Place would have been reserved for guests. The bulk of his property, which included New Place and his London home, Blackfriars gate-house, went to their eldest daughter, Susanna. By common law a widow was then entitled to a third of her husband’s estate and life-long residence in the family house.