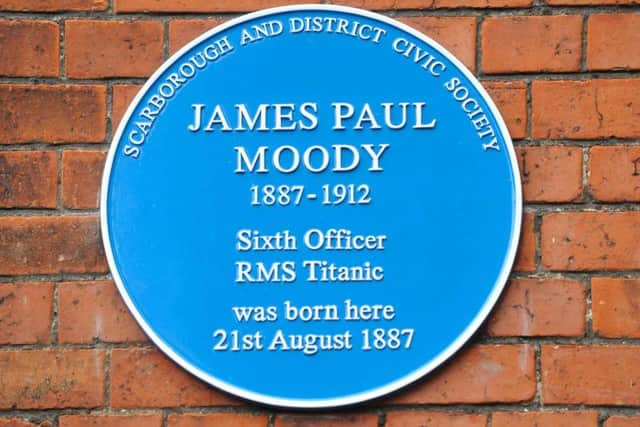

Amazing story of James Moody, the Scarborough hero on the Titanic who laid down his life to save others

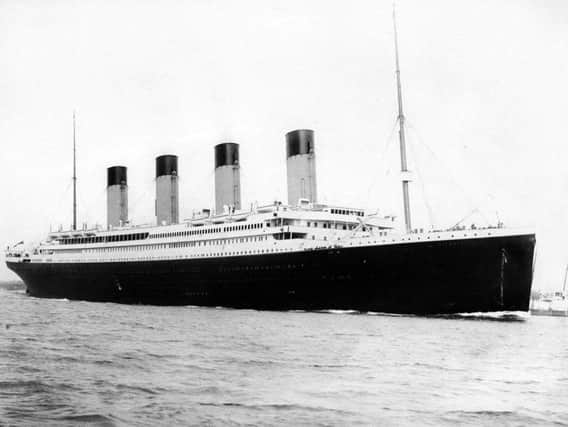

Twenty-four year old Scarborough-born James Moody regarded his promotion to Sixth Officer on the brand new RMS Titanic with mixed feelings. On the one hand, as he wrote to his sister; “My room is no bigger than a broom cupboard.” On the other hand, this truly was a plum job; a prime posting on the biggest and most prestigious ship ever built.

Like the rest of that ill-fated juggernaut’s crew, Moody was there because he was at the top of his game. Born to John Henry Moody and Evelyn Louise Moody, nee Lammin, on August 21st, 1887, he was a graduate of the King Edward VII nautical school in London, where he passed his Master’s Examination in April of 1911. James then served for several months aboard the White Star liner Oceanic, running between Liverpool and New York, before taking up his posting on the Titanic.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Moody family was very well known in Scarborough. James’ father was on the town council, and his grandfather had been the town clerk. One of his ancestors, Charles Bartholomew Moody, was the first coroner of Grimsby.

Another of Moody’s uncles worked as a solicitor in Grimsby. This firm was still in existence at the turn of this century, based at St James House. Back in 1912, this was James Moody’s place of residence.

For the princely sum of around thirty-seven dollars a month, James was responsible for two, four-hour watches each sea day. These were from eight until twelve in the morning, and he had the same hours again in the evening. Additionally, he stood the first of the four so-called ‘dog watches’, between four and five on the afternoon of each day. His place of duty was actually on the bridge of the Titanic.

There is evidence that James felt somewhat isolated on the vast Titanic. His friend Davy Blair, who was the original Second Officer, was not with him, having been replaced in a reshuffle during the ship’s final days in Belfast. And, while Blair no doubt later appreciated the luckiest demotion in maritime history, James still missed

his old friend from the Oceanic days.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAt first, everything on that infamous maiden crossing went deceptively smoothly. For a full five days, the Titanic surged westwards across the calm, sunny ocean. Even in high summer, the Atlantic is never normally calm for more than four full days at a time. Lulled by the good weather, cocooned in the stunning luxury of the ‘Floating Ritz’, spirits on Titanic were high among both passengers and crew alike.

That party was about to end in frightful fashion. James was on the ship’s bridge on the night of Sunday, April 14th, sharing the duty watch with First Officer Bill Murdoch. That bridge was darkened and quiet; the ocean far below it a complete flat calm. Above them, the sky was packed with millions of twinkling stars, a seeming guarantee of good visibility.

Earlier, Moody had telephoned the lookouts in the crow’s nest high up forward, telling them to keep a sharp watch for icebergs and bits of small field ice. The Titanic was now in the region of the Grand Banks of Newfoundland.

No-one was unduly alarmed; this was simply standard practice for this region of water.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAt 11.40, the silence was shattered by a triple chime from the lookout bell, followed by the sharp buzzing of the bridge phone. It was James that answered the call.

“What did you see?”

“Iceberg right in front of the ship!” Seaman Fred Fleet shouted down the line.

James thanked Fleet, hung up the phone, and passed the news on immediately to Murdoch, the ranking officer in charge at that moment.

There then followed a series of shouted orders, clanging alarm bells and urgently flashing lights. For thirty-seven seconds, James Moody watched on helplessly as Murdoch attempted vainly to warp the vast bulk of the Titanic out of the iceberg’s path. As the bow swung to port and out into clear water, it looked at first like a close shave.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was anything but a near miss. The iceberg’s kiss opened around one-third of the Titanic to the ocean. The salt water assassin did its work; the steel hull plates of the Titanic crumpled like so much rice paper.

The impossible had come to pass; the unsinkable ship was doomed.

Stunned and disbelieving, Captain Edward Smith gave orders to uncover, and then load the lifeboats.

The last hours of Moody’s young life passed in a blur. He assisted Chief Officer Henry Wilde in helping to load and lower the pitifully few lifeboats on board. As the band played, white distress rockets clawed at the sky, erupting in a series of deafening booms.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLike the other officers, James Moody’s main concern would have been to prevent a mass panic. He knew that there was a total of 2,200-plus passengers and crew aboard the Titanic that night, and lifeboat space for less than 1,200 of those. In those last awful hours, the design miscalculations of more than forty complacent years fell around Moody’s ears like a series of thunderclaps. But he stuck to his post and, in doing so, was instrumental in saving a great many otherwise helpless people.

As one of the more junior officers, he should by rights have left the Titanic to take charge of some of the boats being lowered into the water. Instead, he sent off Fifth Officer Harold Lowe, one of the undoubted heroes of that night, and returned to help Wilde. Like Wilde, Moody would have been well aware of just how few trained, professional seamen there actually were on board the Titanic.

Despite the freezing cold, he would have been sweating from the sheer, physical exertion of first loading, and then lowering, the big, five-ton lifeboats. As he by turns coaxed and cajoled the frightened passengers to get into the boats, he never once gave a thought to himself.

At about 1.30 in the morning, Captain Smith issued all of his remaining officers with loaded revolvers. There is no evidence that James Moody was even seen to be carrying his.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBy 2.05, the last lifeboat was about to be lowered from the Titanic. It had forty-seven seats; around 1,600 people remained on board.

The crew formed a human chain around it, allowing only women and children through to safety.

Somewhere just aft, Wallace Hartley and his musicians broke once more into the strains of ‘Alexander’s Ragtime Band’.

Along with Murdoch, James Moody was last seen on the roof of the officers’ quarters, trying to free a couple of auxiliary boats that were lashed into place there. Soon after 2.10 a giant wave swept across that roof, and James was never seen again. His body was never recovered.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJames Moody was a young man who was placed into a situation that was nightmarish beyond any adequate description. If he had cracked and broken, it would have been perfectly understandable.

Other men did that night, after all.

Had he left the Titanic in charge of a lifeboat – as he easily could have done – it would have been sensible, even logical. Instead, this incredible young man did no such thing. Faced with his own, almost inevitable demise, he stayed at his post, working tirelessly to save others.

James Moody is not forgotten. There is a memorial plaque to him in the Church of St Martin on the Hill, in Scarborough. It bears these words; ‘Be thou faithful unto death, and I will give thee a crown of life’.

Even more apt is another memorial, raised to him in Woodlands Cemetery. The salutation is simple, and straight to the point; ‘Greater love hath no man than this; that a man lay down his life for his friends’.