Nostalgia: '˜The Hackness Shame'

Of the six there were two members of the Eure family of Malton, Sir William, the brother of Lord Eure, and another William, son and heir of the lord; William Dawnay of West Ayton, who was married to a Eure; Richard Cholmley, eldest son and heir of Sir Henry of Roxby castle and Abbey house, Whitby; William Hildyard of Bishop Wilton; and Stephen Hutchinson of Wykeham Abbey. Apart from Sir William, all were young and boisterous and what they did and said during the next 12 hours came to be known as “the Hackness Shame”.

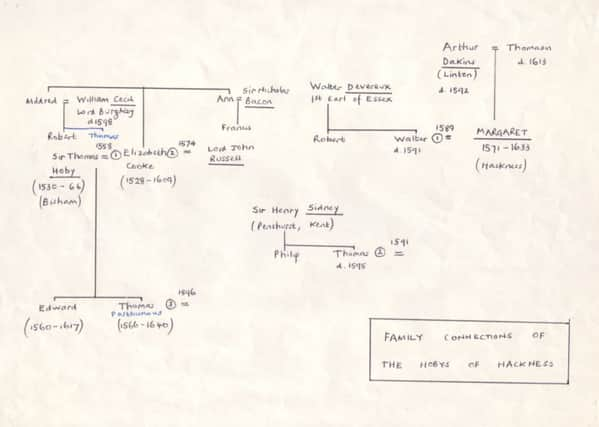

Their unwilling host was Sir Thomas Posthumous Hoby, lord of the manor, and husband of Lady Margaret. Sir Thomas was “Posthumous” because his father, Sir Thomas Hoby of Bisham in Berkshire, had died of the plague in Paris three months before his second son’s birth. Sir Thomas senior was a distinguished scholar, linguist and professional diplomat who had represented Queen Elizabeth at the court of France. Elizabeth was so upset by his death that she agreed to become young Thomas’ godmother.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThomas’ mother, Elizabeth Cooke, was as talented and as well-connected as his father. Her eldest sister, Mildred, was married to William Cecil, who became the first Lord Burghley and the Queen’s Lord Treasurer. Their two sons, Robert and Thomas Cecil, both achieved high offices. Robert became Principal Secretary and Thomas became lord president of the Council in the North at York. Elizabeth’s youngest sister, Ann, was the wife of Sir Nicholas Bacon and the mother of Sir Francis Bacon. So Posthumous Hoby had three cousins who were the most famous in the land. When he was eight years old his widowed mother married John, Lord Russell, the son and heir of the Earl of Bedford, which meant that another of England’s leading peers was his step father. Even when Lady Russell was widowed for the second time she continued to exercise great influence from her London home at Blackfriars.

However, though Hoby mixed with the mighty, he was not one of them. As a second son, he inherited neither estate nor wealth. After Oxford, he served only as a gentleman in the households of great peers such as Burghley and Leicester. Powerful patrons secured him a seat in the Commons for Appleby in Westmorland in 1589 and again in 1593, but MPs received no salary. For his military service in the Low Countries and Ireland, he was given a knighthood, but not the landed estate he needed.

Fortunately, an opportunity came his way in 1595. Lady Margaret Sidney of Hackness was already twice widowed, but she was still only 24. Since the death of her father, Arthur Dakins of Linton near Wintringham, she had become the sole owner of 11,000 acres worth £1,500 a year. In addition to the “town” of Hackness and the rectory of its church, the estate included the villages, farms and woodlands of Langdale, Everley, Broxa, Suffield, Silpho and Harwood Dale, 200 properties and four mills on the Derwent. And like Posthumous, Margaret had been brought up as a strict, puritan Calvinist.

In August 1596, Thomas and Margaret were married in Lady Russell’s London house. It was a puritan wedding: no music, no dancing, only a sermon and a simple dinner.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHoby’s arrival in Yorkshire (“these frozen parts”, as he called them), was calculated to cause the greatest offence amongst the native gentry. When he offered himself for one of the county’s two seats in the Commons in 1597, he was rejected as an upstart and southern carpet-bagger. He had to settle for Scarborough and even there tried to dictate his running mate. That he was also “diminutive”, even “tiny”, prompted scandalous innuendos about his sexual potency, particularly since after four years of marriage Margaret had still not conceived.

The Protestant Reformation had scarcely reached North Yorkshire by 1600. Not least of the reasons why Hoby was “parachuted” into one of the most notoriously “backward” areas in the country was that at Hackness he would become a listening post and give advanced intelligence of Catholic missionary activities. Abbey house, for instance, was a well-known refuge for continental seminary priests.

So Hoby was obliged to give hospitality to his uninvited guests and they deliberately abused it. They played cards and dice knowing full well that Sir Thomas forbade them in his home; their conversation was mostly of dogs, horses and hounds, when Hoby’s sport was restricted to freshwater fish and lawn bowls on his private green; they used the foulest language and drank to excess in the knowledge that this behaviour would outrage their hosts. And during household evening prayers they laughed out loud and stamped their feet. Even the following morning they were still drunk and demanding more wine; and though Lady Margaret was unwell, young Eure forced his way into her chamber to speak to her. When finally they rode away, they threw stones at the Hall’s glass windows, trampled over a newly-laid courtyard, and in the presence of his wife called Hoby a “scurvy urchin” and “a spindle-shanked ape”.

Sir Thomas took his strong complaints to the Court of the Star Chamber in London after he learned that the Council at York would deny him justice. He claimed that the assault had been an intentional abuse of his hospitality, of his religious beliefs, and his authority in the neighbourhood as an officer of the Crown. The culprits denied all his charges in vain. The verdict of the court went against them and Hoby was entirely vindicated.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs Lady Margaret triumphantly recorded in her diary, in May 1602 Lord Eure came to Hackness Hall with £100 in gold “for their riot Committed and unsivill behauour”. On this occasion she made no attempt to disguise her joy: “and so it fell out that, as it was done in the sight of our tenantes...which I note, as seeinge the Istuice and mercie of god to his servants in manifestigne to the world, who litle regardes them, that he will bringe downe their enemes unto them”. Though we have no record of the details of the judgement on earth, it seems that the Eure estate was to pay the Hackness lordship £100 a year in perpetuity! Of the other miscreants, 400 years later, Lord Downe of Wykeham Abbey still pays £60 annually to Lord Derwent for “the Hackness shame”.

[next week: Hoby and Scarborough]