Nostalgia: Scourge of the black death

One of the most detailed and accurate descriptions of the onset and progression of what came to be called the black death comes from an Italian source:

Those of both sexes who were in health, and in no fear of death, were struck by four savage blows to the flesh. First, out of the blue, a kind of chilly stiffness troubled their bodies. They felt a tingling sensation...The next stage took the form of an extremely hard, solid boil...as it grew more solid it caused the patient to fall into a putrid fever with severe headaches. In some it brought spitting of blood, in others swellings and intolerable pain.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe “solid boil”, or inflamed swellings in the groin and armpits, the most characteristic symptom, is also known as a bubo, which explains the term bubonic plague. In this case, death followed in three to five days or a full recovery occurred. However, if the plague bacteria affected the respiratory system and thereby led to “spitting of blood”, pneumonic plague was certain to kill even more quickly. Thirdly, when a victim died within hours of the onset of illness, the plague bacteria had passed directly into the bloodstream causing lethal septicaemia.

As for the causes of the black death, it was not discovered until as late as 1894 that the culprits were fleas which, hosted on black rats, transmitted the disease to humans after they had killed the rats. Whether the black death was entirely bubonic or also pneumonic or septicaemic remains a disputed question among medical historians.

We know that the plague was first brought to England by a shipload of refugees from Calais who landed in Dorset, and that successive epidemics were worst and most common in seaports, especially London, Newcastle and Hull. However, between 1598 and 1605, Yorkshire’s north-east coast, from Runswick Bay to Scarborough, and many local inland villages were badly affected.

Runswick’s register records the death of 60 parishioners in what was only a small fishing village. No complete, continuous parish registers of baptisms, marriages and burials survive for other small local communities, but Lady Margaret Hoby’s diary provides some evidence. On September 4, 1603, she wrote: “we hard that the plauge was spred in Whitbye”; on the 10th, hearing that refugees from Whitby had carried the infection to Harwood Dale, she, her mother and husband fled to Place Newton and then Thorpe Bassett; on the 27th she wrote: “...the sickness was freared to be at Robin Hood bay”; on October 23: “this day I hard the plauge was so great at Whitbie that those who were cleare shutt themselves up”; on May 17, 1605: “Snanton, Brumton and Eberston were restrained for feare of the plague”; and finally, May 28, 1605: “Hunenbye was infected”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSurprisingly, Lady Margaret made no reference to the plague at Scarborough, perhaps because by the time that her diary began in August 1599 the worst of it there had passed through the town.

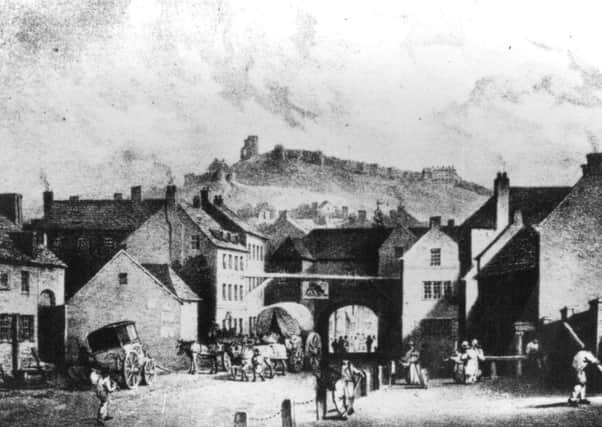

The first indication that Scarborough had the plague was an order from the Privy Council in London sent out in 1598. Since the town had been visited by “a dangerous infection whereby great mortalitie did ensue”, Seamer’s weekly Monday market was permitted to re-open temporarily.

At Scarborough infection was subdued quickly and effectively because its governing authority had the means to shut down its Thursday and Saturday markets and to control the movement of goods and people arriving by sea. Before any crew or cargo were allowed to come ashore, the master was required on oath to swear before one of the bailiffs that his ship was free of the plague. Though there was no understanding that the disease was transmitted by fleas from black rats, it was generally known that ships were common carriers.

The outbreak of black death during the years 1598 to 1605 was so severe and widespread that in 1604 Parliament granted new, additional powers to combat it. As acting justices of the peace, Scarborough’s two annually elected bailiffs were given the right to levy rates for the maintenance of the sick and destitute and to deter breaches of quarantine by whipping or even hanging offenders.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn the absence of a surviving, intact, continuous parish register for these years, it is impossible to calculate the demographic impact on Scarborough of this particular incidence of plague. We have only a transcript of the original for the year ending March, 1603, which records the burials of 40 parishioners at St Mary’s. This number was only one fewer than the record of baptisms for the same year, which suggests the presence of a fatal disease in the town.

In normal circumstances at this time, like Whitby but unlike most seaports and inland towns, Scarborough enjoyed a relatively healthy environment. Both did not need immigrants from the rural hinterland to maintain or increase their resident populations. When there was no evidence of epidemic, the death rate in both was low because natural drainage was provided by steep slopes running down to the tidal shore. In the absence of man-made surface or underground sewers, gravity saved the people of Scarborough and Whitby from water-borne diseases such as typhoid.

In Scarborough’s case, householders also had the benefit of a reliable, adequate supply of clean, piped drinking water brought underground from Falsgrave’s springs. The Franciscan friars had gone, but their medieval system was still rigorously serviced by the corporation. Three stone troughs, called the upper, middle and lower conduits, situated at the junction of Newborough and St Thomas Gate, St Sepulchre Gate and the Dumple (now Friargate) and the top of West Sandgate, next to the Butter Cross, were freely accessible during daylight hours and locked and guarded at night.

Finally, with fewer than 2,000 residents in Scarborough and Falsgrave, the population was small enough and sufficiently concentrated to be effectively governed by a self-elected Common Hall enforcing traditional “pains” and laws. Its appointed officers kept the gutters and streets clear of offal, refuse and waste and protected market customers from being poisoned or cheated by butchers, fishermen, brewers and bakers.

[Next week: How the Plague returned to Scarborough]