Nostalgia: The rules of Tudor society

You might rest your forearms but not your elbows on the dinner table; standing with your arms crossed was then thought foolish; and standing with your arms behind your back was acceptable for a tradesman, not a gentleman.

Even the way you walked betrayed your occupation; labourers stooped with work-worn backs; ploughmen plodded slowly, heavily and deliberately in a straight line; and shepherds were light-footed and nimble.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCountry people were recognised in towns by their slow gait, whereas young gentlemen swaggered through the streets, drawing attention to their swords, purses and daggers.

By the time that they were four or five years old, boys and girls were expected to behave formally and politely in the presence of seniors. For boys, doffing the cap was not just compulsory: it also had to be performed in a prescribed form and style. Bowing properly demanded practice and good balance. Girls kept heir heads covered, their eyes lowered, and their knees bent.

But the clearest indication of a man’s class was the level of his literacy and numeracy.

Most Tudor boys and girls were taught to read if only the Ten Commandments, the Lord’s Prayer and the Catechism, now that they were all in English, not Latin; but at the lowest rung of the social ladder, children were instructed to learn them by rote and recitation. Writing was a different matter.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPloughmen and shepherds did not need to write, not even their own names. What documents would they ever have to sign?

Whereas we learned to read and write simultaneously at home and at school, then writing came later after reading and often beyond the age when children were put into full-time work by their parents or their masters and mistresses. Most apprenticeships began about the age of seven. In fact, the Statute of Artificers of 1573 made seven years a national minimum for apprenticeships. It also laid down their maximum hours of work, from dawn to dusk during winter months and only up to eight in the evening during summertime.

Apprentices were also to be allowed breaks – an hour for dinner and three other half-hour breaks or “bevers” or beverages.

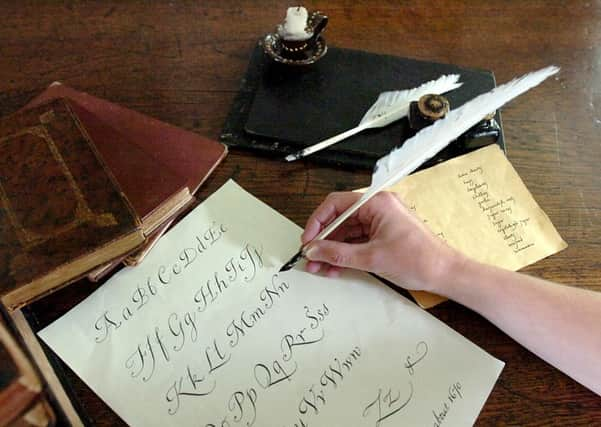

A school where writing was taught necessarily had to have more resources. At first, letters could be drawn in sand or chalked on slates, but soon pens, ink and paper were required and all of these were expensive to buy. Good, indelible ink was especially costly.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdQuill pens, fashioned from goose feathers, were cheaper than metal nibs of brass or silver, but soon wore out and had to be frequently shaped with a penknife. The best penknives were made in Sheffield.

Apart from destitute orphans, who were put into apprenticeships by poor law authorities when they reached the age of seven, only the sons of guild craftsmen, yeomen farmers and prosperous husbandmen could aspire to prolonged education and training. Their masters had to be paid a lump sum in advance.

In Scarborough’s corporation records of the early 1600s there are dozens of apprenticeship indentures signed by fathers and masters. The great majority bind the boys to the art and mystery of a master mariner, several to that of a shipwright, boat-builders, ships’ carpenter and rope-maker, and a few to a fisherman. The trade and faculty of a joiner, the art and science of a woollen draper and the trade and faculty of a weaver are also reported.

All these occupations are predictable for a seaport and town like Scarborough. What is surprising is that so many young apprentices came from such distant homes, not just from Seamer, West Ayton, Scalby, Cloughton and Raincliffe Gate, but from Pickering, Malton, Lythe, Weaverthorpe, Wrelton and Patrington. The only apprenticeship offered to young girls until they were 21 or married was “huswifrye”. Ages on entry ranged from as young as five to as old as 16.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn some indentures there was an explicit obligation for the master to provide schooling for his apprentice and his wife to give moral guidance to him. There was no guarantee that the terms of the contract would be honestly and fully honoured – apprentices complained of exploitation, physical beating and neglect and masters of insubordination, idleness, theft and immorality. From evidence elsewhere we also know that many apprenticeships did not run full term, but for the sons and daughters of the poor apprenticeship was their only route to material success and higher status.

Parents who did not have the means to pay for an apprenticeship could put out their sons and daughters as servants on an annual agreement. Masters and mistresses gave free bed and board in their own households, so wages were very poor. Boys were put to field work or animal care, girls did domestic, kitchen and dairying chores. At harvest and shearing times, the whole household would be working together. Particular posts commanded higher wages. A ploughman had the most skill and needed the most strength and stamina; a dairymaid had the cleanest and least arduous job.

Apprentices who had served their term and servants who had reached their twenties might not be able to write, but they probably read the Bible and public notices and possessed basic numeracy skill. By their twenties they would be looking for a spouse and a home of their own. On average, ages at first and usually only marriage were 24 for women and 26 for men.

Since adolescents of both sexes lived closely together under the same roof and in houses where chambers were separated only by curtains not corridors, it was unlikely that either bride or bridegroom were still virgins on their wedding day. In Yorkshire, as many as a third of brides were pregnant when they were married in church.