Are you superstitious ? Yorkshire author Sally Coulthard's new book reveals why we fear the number 13, and other folk beliefs

and live on Freeview channel 276

Yorkshire author Sally Coulthard did and her investigations into the superstitions and traditions we observe in our homes and elsewhere have led to one of the most fascinating and entertaining books of last year.

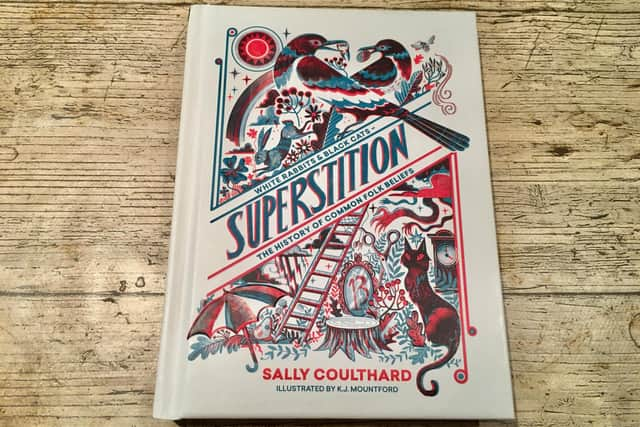

Superstition – the History of Common Folk Beliefs, which is illustrated by Karl James Mountford and published by Hardie Grant, £12.99, is full of fascinating facts backed by careful research.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSally, who lives in North Yorkshire, read Archaeology and Anthropology at Oxford University, which she says are “subjects stuffed with ancient stories and strange legends”.

However, it was the witches' marks in an old stone barn on her farmstead that prompted her to turn detective.

The number 13.

She says: “While most superstitions are harmless, some are causing damage. Take the number 13 for example. A recent survey found that, in the UK, if you live at number 13 your house is likely to be worth an average three per cent less than your neighbours’ homes.

“That may not sound like much but when you factor in the average house price, that equates to a £9,000 hit.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“A third of people in the survey also said they would be unlikely to buy a house with the number 13, while a quarter saying they wouldn’t exchange contracts, complete or move house on the 13th day.

“It’s incredible to think that the single biggest financial commitment people are likely to make is being influenced by superstition.”

Sally’s research also revealed that superstitious people also tend to be worriers or control freaks and young people and women are, generally, more superstitious than older people and men.

Here are some superstitions explained by Sally, and you can find many more in Sally’s book.

Horseshoes.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt’s not unusual to find a “lucky” horseshoe above a door. How they became associated with luck is tricky to establish but one theory links to the legend of Saint Dunstan, Archbishop of Canterbury in the 900s, who was said to have tricked the devil.

Dunstan, who was also a blacksmith, was asked by a stranger to shoe a horse. Spotting that the man had cloven feet, he shoed the Devil instead, causing him great pain. Dunstan agreed to remove the horseshoe but only if the Devil promised never to enter any building that had a horseshoe over the door.

However, this superstition may go even further back to 6,000 years ago. A folktale exists in 30 different languages from India to Scandinavia, where a blacksmith strikes a deal with the Devil, exchanging his soul for the power to weld any material.

The Devil agrees but is tricked and welded to an immovable object, rendering him powerless, so the horseshoe is a symbol of man’s ability to thwart supernatural forces.

Witches' marks or hexfoils.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThese are found in barns,cottages, churches and other buildings to ward off evil spirits and bring good fortune.

They were often mistaken for mason’s marks until 1967 when Cambridge academic Violet Pritchard published a paper on them.

The medieval scratchings come from a time when belief in witches and superstition was part of everyday life. Men and women would carve specific symbols as an act of devotion or to evoke good luck. Most common is the daisy wheel or hexfoil, a pattern whose endless lines were supposed to confuse and trap evil spirits.

Other common marks include pentangles, concentric circles and the letters VV or AM, often intertwined, which refer to the Virgin Mary.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOther marks have been uncovered, including sailing ships, shoes, windmills, demons and musical notes, all representing voices from the past hoping for the safe return of a ship, a plentiful crop or protection in the afterlife.

The best place to find these marks are entrances, around doors and fireplaces or even on roof timbers.

Dried cats.

Often found tucked away in historical buildings, many have been preserved by smoking or desiccation and appear everywhere from the UK to Gibraltar, Sweden and the eastern US.

Many are from the 17th century, a period obsessed by witchcraft, when it was believed that evil spirits taking the form of a rat, mouse or bird, might enter the building.

Dried cats were thought to war the spirits off.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOther animals have also been found hidden. One remarkable Tudor find from Lauderdale House in London revealed four hens, a candlestick, a wine glass and two odd shoes. The bricked-up recess also contained an egg, suggesting that at least one of the hens was alive when it was hidden.

Touch wood.

In Britain the oak tree played a central role in Druid worship so it’s not difficult to see how trees became places of truth-telling, prophecy and worship.

The practice of touching wood may have its origins in these early ceremonies – people making a wish or asking for spiritual intervention by the tree spirits.

The modern use of “touch wood” still holds on to the idea that people shouldn’t get ahead of themselves, lest the spirits or fate decide to teach them a lesson.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSo we “touch wood” as a charm against our own boasts or a run of good luck. Such ideas tap into the deep-seated notion that we as humans don’t really feel in control of our destiny and that fortune or fate will punish those who express their good luck too emphatically.

Curiously, the Italians say “touch iron”. It is an abbreviation of “touch horseshoe”.